Air Conditioning and the Climate Crisis

At the time of publication, it is mid-July and Ireland is about to get hot – really hot.

No matter what record temperatures are likely to be set in Ireland and around the world this year, we can say with all certainty that this is likely to be the coolest summer that you’ll experience for the rest of your lives.

The arrival of summer also means a mad rush to buy the last available desk fan to keep you cool at night, but more and more Irish people are electing to make the switch to air conditioning – sadly without the necessary information to understand the wider climate implications of this choice.

Find out how keeping cool this summer could directly lead to a hotter future.

Aircon Paradox

Sales of air conditioners are rising rapidly in Europe as we experience hotter and hotter summers year-on-year, and the industry is forecasting an 88.9% growth in sales over the next decade.

This is an understandable response to increasing temperatures, but most people do not understand that this is leading to more heating and yet more record-breaking temperatures.

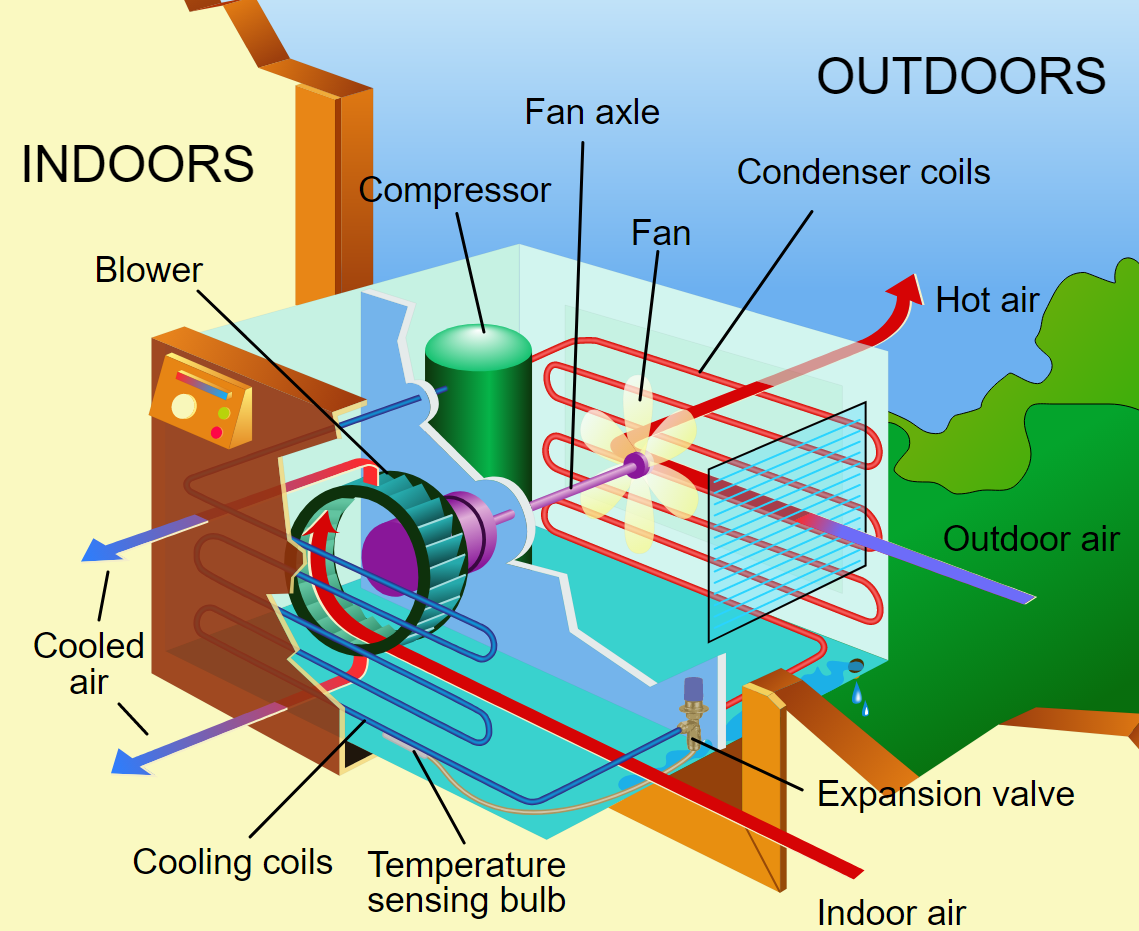

Air conditioning works by taking hot air from the interior of buildings and emitting it into the surrounding outdoor environment.

This expulsion of hot air is worsened by the vast amounts of energy needed to run AC units – which predominantly comes from fossil fuels, meaning that the hot air emission are coupled with shocking levels of CO2 emissions.

This has major effects both globally in the long-term, and locally in the short-term.

In fact, a 2014 study from the Arizona State University found that the hot air expelled from AC units raised local temperatures by as much as 1.5°C during night time hours.

The use of air conditioners is projected to rise significantly as the Climate Crisis worsens and extreme heat events become more common. Credit: UN Environment Programme & IEAE

When coupled with the heat island effect – where the use of man-made materials in urban areas traps heat for longer and increases local temperatures – this could lead to cities being around 3°C warmer than their surroundings.

This compounds the record-breaking temperatures that are becoming more common due to the Climate Crisis, meaning more people are likely to suffer – or die – from heatstroke and other heat-related conditions.

In short – air conditioning will lead to you being hotter, rather than cooler, in the long-term.

Energy Inefficiency

Air conditioners are incredibly energy-intensive, using vast amounts of electricity to cool the air and circulate it in people’s homes and in businesses.

A great example of this at scale can be seen in New York City. On a typical day, the city demands around 10,000MW of electricity every second, but this rises to over 13,000MW every second during a heatwave, according to Con Edison – the company charged with running the city’s grid.

Not only does this mean an increased use of fossil fuels to meet the power demands placed on the grid by air conditioning, but it also means that the grid is more likely to fail, with high demand and extreme temperatures causing blackouts.

In 2006 such a blackout during a heatwave led to the deaths of 140 people and left 175,000 people in Queens without power for a week.

The Guardian reports that a small unit cooling a single room, on average, consumes more power than running four fridges – while a central unit cooling a typical house uses more power than 15 fridges.

This level of energy inefficiency coupled with widespread use meant that, in 2019, the US used more electricity for air conditioning alone than the UK used for the whole country for a whole year.

The International Energy Agency has predicted that, as the Climate Crisis worsens and air conditioners become more widespread, they will account for 13% of the world’s electricity consumption and produce 2bn tonnes of CO2 per year by 2050.

That’s equivalent to the carbon footprint of India today – the third largest CO2 emitter in the world.

While it is possible to run air conditioners on renewable energy, we simply do not create enough renewable energy to meet current demand.

Remember that, in Ireland, just 13% of energy produced in 2021 came from renewable sources, according to the SEAI.

Adding more demand will only increase our dependence on fossil fuels – and worsen the Climate Crisis further.

Waste Gases

Air conditioning units kick out a vast amount of hot air into the surrounding area. This can have the effect of heating urban vicinities by as much as 1.5°C during night time hours. Credit: Wikicommons

Even when air conditioners are taken out of use they can still have a significantly detrimental impact on worsening the Climate Crisis.

The chemicals used in AC units to cool the air – known as hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) – are incredibly potent greenhouse gases, and have a warming affect many thousands of times worse than carbon dioxide when released into the atmosphere.

In fact, releasing just a kilogram of HFCs does as much damage as releasing a ton or more of carbon dioxide, according to the Natural Resources Defense Council.

HFCs are also the fastest-growing class of greenhouse gases – thanks, in part, to increased use of air conditioning.

These refrigerant gases slowly leak into the atmosphere over the life of the air conditioner, but they escape en masse when the air conditioners are thrown away or destroyed. This is often overlooked compared to the relevant convenience of installing an updated unit, but these invisible gases are actively making our world warmer and worsening the Climate Crisis.

This deep-dive from Scientific American offers great insight into this issue, and the importance of addressing it before we run out of time.

Same city, same day, same time - designing our cities to be cooler, especially with increased use of plants and green spaces, offers significant benefits in a warming world.

Accessible Alternatives

The Climate Crisis is already responsible for the deaths of more than 5 million people worldwide each year, and the World Health Organization estimates that the increased incidence of extreme heatwaves will lead to an additional 250,000 deaths each year between 2030 and 2050.

We already know that air conditioners increase local temperatures and worsen the Climate Crisis, while also being prone to higher rates of failure in extreme heat, so what’s the solution?

Using better building materials that have a higher ‘thermal mass’ – their ability to absorb and release heat slowly – will help to reduce temperature fluctuations. Glass-fronted buildings are an example of how terrible modern architectural design is for trapping and maintaining heat.

Having good insulation in your home will not only save on your energy bills but also help to keep the heat out in the summer and keep the heat in during the winter months. This is a cheap but sure-fire solution.

Meanwhile using better shading and ventilation will help to lower indoor temperatures and ensure a through-flow of cool air.

On a larger scale, removing tarmac from around your home can reduce the heat island effect, while planting more trees can have a major impact on lowering local temperatures.

As with every aspect of the Climate Crisis, we already have the all the solutions – and it typically comes down to doing a lot more with a lot less. The reality is that we don’t need air conditioners in Ireland, and we have cheaper and more effective ways to stay cool that won’t also worsen extreme heat in the years to come.

What To Read Next

Ecocide: Making Environmental Destruction A Crime

New legal definitions could have major implications for holding corporations and governments criminally accountable for offences against the environment

RTÉ and the Climate Crisis

Eight months on from Jon Williams' public apology for RTÉ News' failure to properly cover the Climate Crisis, we investigate what has changed, and how far the national broadcaster has to go