Hybrids: A Harmful “Green” Myth

While we have previously and extensively written about the myth that hybrid vehicles are in some way “green” or “sustainable” a new report published today has given us cause and further evidence to dispel this illusion.

How harmful are hybrids?

A collaborative study by Transport and Environment and Greenpeace has found that carbon dioxide emissions from plug-in hybrid vehicles are up to two-and-a-half times greater than official tests and manufacturer marketing suggests.

While official tests record plug-in hybrids as emitting an average of 44g of CO2 per km driven on closed circuit conditions, today’s report found that the same vehicles produced 120g of CO2 per km when driven on real-world roads.

This data was gathered from over 20,000 plug-in hybrid drivers around Europe, and demonstrated that the average plug-in hybrid car would produce around 28 tonnes of CO2 in its lifetime – only offering a small reduction on the 39-41 tonnes of CO2 produced by the average petrol or diesel car, or the 33 tonnes produced by non-plug-in hybrids.

Rebecca Newsom, Greenpeace’s Head of Politics, stated the following when speaking to the BBC: “They may seem a much more environmentally friendly choice, but false claims of lower emissions are a ploy by car manufacturers to go on producing SUVs and petrol and diesel engines.”

Separating marketing from reality

To better understand where the difference in these figures comes from, we need to look how emissions tests are managed, and who they are run by.

Typically they will be conducted with the plug-in hybrid on a full charge and run at low speeds to ensure that the car operates using only its electric motor for the longest possible time before it switches to using its petrol/diesel engine, once it reaches a certain distance or speed.

This creates a more marketable result that car companies can use to promote their hybrid lines as “green” choice vehicles. However, it doesn’t reflect how these vehicles will be used in the real world.

Screenshot of Toyota’s C-HR advert

For example, Toyota’s current TV advert for its C-HR carries a disclaimer in the smallprint, stating that their model “spent an average of 56% of its time in electric mode in test drives covering 416,000 miles at an average speed of 22mph”.

When did you last travel at an average of 35khp over a distance of 416,000 miles?

This approach of misleading consumers by car manufacturers has been coupled with aggressive marketing to companies who operate large fleets, with the aim of those businesses being able to publicly state that they are “going electric” or reducing their carbon footprint.

In reality it is commonplace to see many of these plug-in hybrids returned with their chargers still in their original packaging and completely unused – having been run solely on fossil fuels and offered no emissions reductions.

“A hybrid will be kicking out at least 40-70% of the emissions of a petrol or diesel car

Wolves in sheep’s clothing

While many hybrids are marketed as being “electric”, this is incredibly misleading as they predominantly run on petrol or diesel for the majority of their use, and therefore create harmful emissions that contribute to climate change.

Hybrid manufacturers are trying to tap into the incredibly high demand for fully electric vehicles by marketing them as something they are not.

With the impending ban on fossil fuel vehicles due to come into effect in Ireland in 2030, the development of hybrid vehicles allows manufacturers to effectively sell you two vehicles rather than one – a hybrid now (which will be banned in the near future) and then an EV when the ban on hybrids comes into effect.

In the meantime, the hybrid will be kicking out at least 40-70% of the emissions of a petrol or diesel car, and will have created 15% more emissions in its manufacture than a battery electric vehicle would have, according to a study by the Low Carbon Vehicle Partnership in collaboration with Ricardo.

Furthermore, while battery electric vehicles can be charged at home and by renewable energy, hybrid vehicles still require fossil fuels. This means that they require oil to be extracted, refined and transported from around the world, creating untold emission levels in the refinement process and during transport to you – known as fuel miles.

And if that doesn’t convince you, hybrids still require you to spend your hard-earned money on petrol or diesel – which is significantly more expensive than electricity.

Simply put, battery electric vehicles create no emissions themselves, while hybrids continue the same cycle that petrol and diesel vehicles do. Can’t tell the difference? Just check to see if it has an exhaust – if it does, then it’s a hybrid.

What’s next?

We have long supported calls to ban the sale of hybrid vehicles in 2030, alongside the impending ban on the sale of new petrol and diesel vehicles.

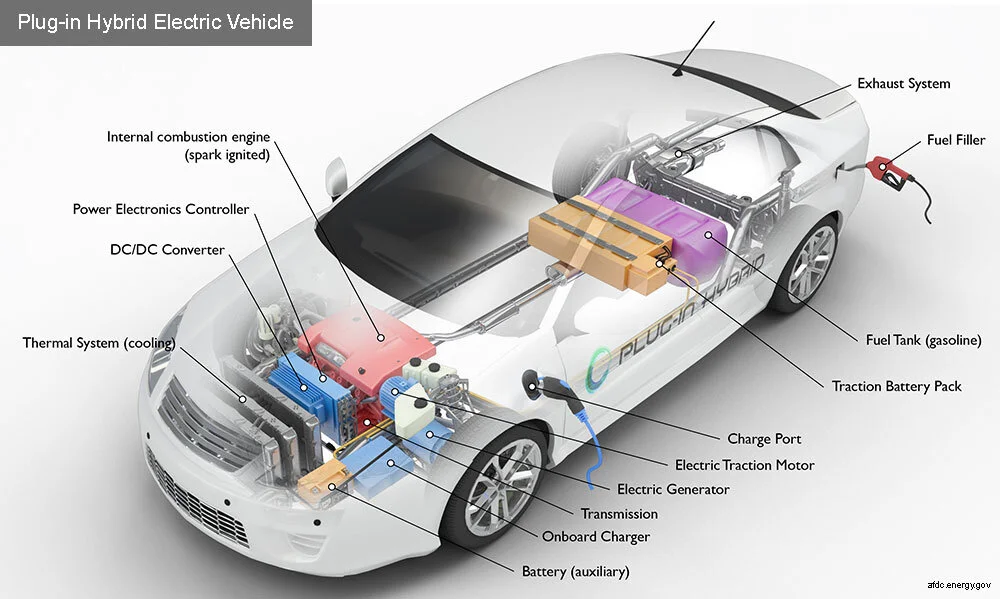

Credit: US Department of Energy

With Ireland producing the third highest emissions in the EU, we need to make a stand and act to reduce the harmful pollution that our country generates – with road transport responsible for 25% of all emissions worldwide, and 60% of Ireland’s cars made up of harmful diesels, we cannot shy away from taking meaningful climate action.

As we cannot rely on manufacturers to accurately report on the emissions of their vehicles, we hope that the Irish government will take action to educate the public and protect them – and the environment – from harmful vehicle emissions by banning hybrids alongside petrol and diesel vehicles.

For more information on this topic see our story on Unveiling The Hybrid and “Self Charging” Myth

What To Read Next

SUVs Are Killing The Planet

SUVs are twice as likely to kill a pedestrian in a collision and are the second largest cause of the global rise in carbon dioxide emission over the past decade

How Car Makers Are Skirting Emissions Regulations

Discover how car manufacturers are pooling their emissions in order to avoid fines and the implications of this for electric cars and the Climate Crisis