Reforestation & Veganism Are Anticolonial Acts

In the face of the Climate Crisis, we are presented with a choice of how we want the future to be. Do we want to live in a sustainable world that is habitable for us and the creatures that we share this planet with, or do we want to repeat the same old mistakes?

While we have all the tools and knowledge that we actually need to overcome the Climate Crisis, it is vital that we change systems and attitudes too, so that we can show the positive opportunities that will arise from change – and just how poorly current systems work for us and ecology.

In many ways, the Climate Crisis is predicated on the continuation of hundreds of years of oppressive colonisation. It requires that native peoples – typically in the Global South – are subjugated, with nature exploited to fulfil the wants and greed of the Global North – the modern day occupying force.

Yet, the people of Ireland should know as well as anyone the impact that colonialism has on a culture and its people – and why we, ourselves, need to stop being an oppressive force against other people around the world.

Today, we look at how reforestation, rewilding and a vegan diet can be a radical act of anti-colonialism.

Utter Deforestation

To put this article in context, in 2022 Ireland holds the shameful record of having the lowest forest cover of all European nations, according to Teagasc.

Just 11% of the land is covered in woodland, while the average across the EU is 33% – and even then this hides that fact that just 2% of our paltry amount of woodland is comprised of native forests.

Meanwhile, the average person in Ireland has a carbon footprint nearly three times higher than the average person on Earth – and 55% higher than the average person in the EU.

So how did we get to this state, and what impact has it had on Ireland’s people, nature and culture?

Look Back To Stride Forward

Trees have always been a vital part of Irish identity.

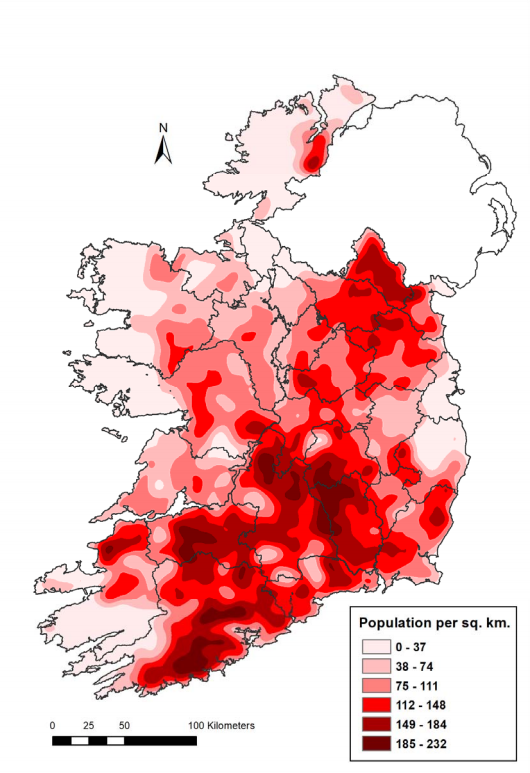

Graph of cattle population density in Ireland. Meat and dairy production is driving continued deforestation. Credit: Agriland

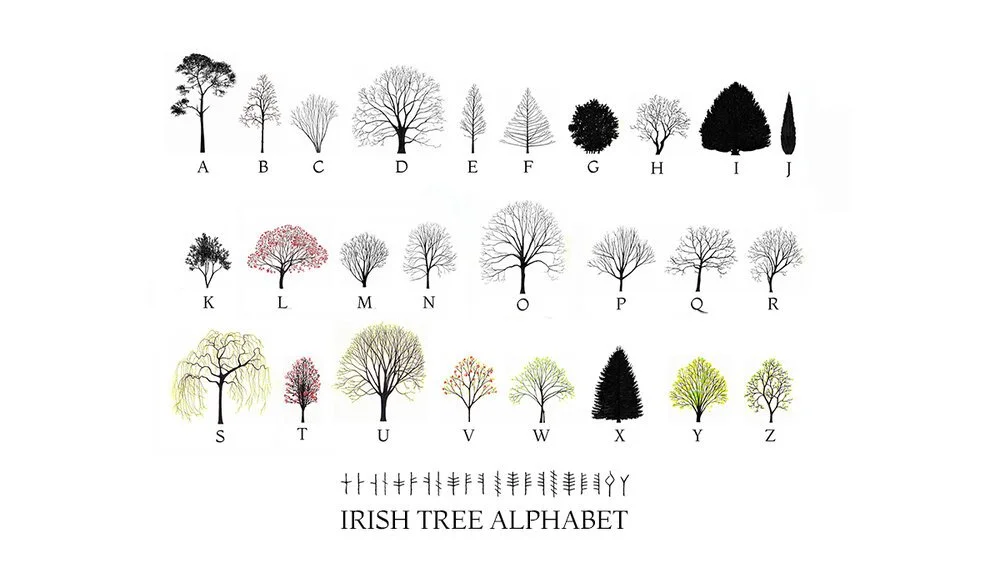

In fact, so entwined was the Irish identity with woodland, that trees were central to the naming of Ogham letters – with eight of the 20 letters of the early Irish alphabet named after native trees.

It is clear too from Brehon Laws that trees were a prized cultural item, with many species specially protected from unlawful damage, such as branch-cutting, barking or base-cutting, and subject to a range of punishments.

This ubiquitous appreciation and importance of woodland can also be seen in the Irish language and the naming of settlements that still exist to this day.

“Coill” – the Irish for wood – was later changed to “Kil” to make it easier for occupying British forces to pronounce. The prevalence of place names with “Kil” prefixes, such as Kildare and Kilkenny, show the importance of forest areas to Irish people before colonisation.

Trees not only helped to define the naming of the early Irish alphabet, but also its design - with Ogham letters following the shapes of the trees they were named after. Credit: Katie Holten

The same can be seen in “Ros” prefix, which was also used to describe woodland, and can be found in the likes of Rosscommon, Roscrea and Rossmore. These places were named for the live-giving properties afforded by the forests to the people who settled in their midst.

This changed with the invasions of Ireland by the British, who saw the forested lands as a barrier to the subjugation of the Irish people and the exploiting of Ireland’s resources.

The Topographia Hibernica (1187) states: “The Irish are a rude people, subsisting on the produce of their cattle only, and living themselves like beasts – a people that has not yet departed from the primitive habits of pastoral life [..] Their pastures are short of herbage; cultivation is very rare, and there is scarcely any land sown […] The whole habits of people are contrary to agricultural pursuits.”

Therefore, we can understand that exploiting the land was a concept imported by those colonising Ireland, while those who lived here before were doing so more in harmony with nature.

Oona Frawley in her book Irish Pastoral: Nostalgia and Twentieth-Century Irish Literature suggests that, for the occupiers, the “uncultivated” state of the Irish people and their land meant that taming the landscape would result in taming the people.

We can see this reflected in the language used to describe the Irish people by the occupying forces, who referred to the native peoples as ‘Cethern Coille’ or ‘Woodkerns’.

The Woodkerns were so named due to their military tactics which used forest cover to ambush British forces. This resulted in direct orders to deforest large swathes of the nation, so that the British could exert military dominance. This is reflected in a 17th Century English proverb:

“The Irish will never be tamed while there are leaves on the trees”.

Once the military threat from Irish people subsided, the English invaders began to focus their efforts on the economic benefits of deforestation, and how this could be used to quell hostility from the oppressed people of Ireland.

In his 1596 pamphlet A View of the Present State of Irelande, Edmund Spenser described the economic benefits of Irish soil as “good and commodious” – while the density of Irish woods “was to be deplored but also welcomed” – deplored for the fear posed by the untamed landscape [and people] and welcomed for its economic value.

Deforestation became so rapid that, by 1600, less than 12% of Ireland was covered by forest.

Ireland experienced the most extreme rates of deforestation in Europe over the course of 900 years, driven by colonialism. Credit: Environmental Engineering Institute, Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne

As Britain laid the groundwork for its globe-spanning empire, the deforestation of Ireland only accelerated, and by 1656 just 2% of the land had forest remaining. Sadly this is the same percentage of native woodland that still stands to this day.

The impact of rampant deforestation in England led to Ireland becoming the primary source of wood to support Britain’s aspirations for expansion, with whole forests destroyed to supply wood for the Royal Navy’s ships, barrels and to make charcoal for gunpowder.

So prized was Irish wood, that the roof of Westminster Hall was constructed from wood taken from native Irish forests near to where Phoenix Park stands today, while vast quantities of ancient Irish oak were exported to rebuild London following the Great Fire of 1666.

So extensive was the destruction and the confiscation of land by the British, that by the end of the 17th Century over 1.5 million of Ireland’s 2 million acres had been transformed into plantations – thereby fulfilling the ambitions of productive land set out by Gerald of Wales in Topographia Hibernica.

The destruction of Irish forests was a subjugation of Irish nature and a deliberate attempt to homogenise the lands of Ireland to reflect those of mainland Britain – resulting in the extinction of diverse native fauna such as wolves, capercaillies, red squirrels, boar, great spotted woodpeckers and the Irish wolfhound.

When Irish State forestry began in 1903, only 69,000 hectares of Ireland’s ancient forests were left – accounting for around 1% of the total land area of Ireland. Even then, attempts to manage forestry by the State were focused solely on their financial, rather than ecological, value.

This attitude of exploiting woodland continues to this day – with the vast majority of forest in Ireland being non-native species, specifically grown for the purpose of chopping down for financial gain. In fact, around 60% of Ireland’s forest area is comprised of non-native species.

Worse still, 11% of forestry in Ireland is monoculture plantations, which are inhospitable to naitve wildlife – in the same way that the plantations of Ireland were designed to be inhospitable to the Irish people.

It is ironic then, that in 21st Century Ireland is still considered one of the largest exporters of wood to the UK – according to the Department of Agriculture, Food and Marine Forest Statistics – Ireland 2019.

There is some hope, however, to be found in Scotland’s efforts to reforest and rewild its landscape, which have accelerated in line with the increasing push for independence as a nation.

Veganism Is Revolutionary

So what does the history of Ireland’s deforestation have to do with plant-based diets?

It is clear that British colonial rule was responsible for the devastation of Irish forests, in part to secure a supply of lumber and other products – but also to support the growing appetite for meat in Britain.

As forests were felled, fields took their place, and cattle were introduced in their millions. Today there are more than 7.3 million cows in Ireland – significantly outnumbering the human population of the Republic of Ireland, and accounting for massive greenhouse gas emissions.

Our meat-heavy diets are responsible for agriculture comprising the single largest source of CO2e emissions in Ireland - and vast quantities of methane. Credit: EPA

In fact, 35.3% of Ireland’s total CO2e emissions come from the agriculture sector – that’s 15% more than the entirety of the transport sector – and our mass farming of beef and dairy is a leading source of incredibly harmful methane emissions.

And yet, much of our meat and dairy is still exported to the UK, as capitalism perpetuates the shackles of colonialism. In 2021, Ireland produced around 80% of the beef imported by the UK, and is the largest source of dairy imports for the UK.

By pursuing plant-based diets, we will be breaking free of thousands of years of exploitation of the Irish landscape and reduce the amount of land required to farm, which in turn will enable us to reforest and rewild the nation.

This will have vast dividends in meeting our emissions targets, while also supporting greater biodiversity and bioabundance in the process.

Restoring native flora and fauna is a distinct act of anti-colonialism, and a way for Ireland to hold itself accountable for the greenhouse gas emissions that it perpetuates and which threaten the people, nature and cultures of nations in the Global South.

Do we want to perpetuate the sins of the past, or draw a line under them in order to establish a more sustainable, greener future?

The simple act of switching to a plant-based diet could be considerably more radical than you might think.

References

The following were important resources in the writing of this article:

Wood you like to know where the trees went? – Trinity News – 2019

Despirited Forests, Deforested Landscapes: The Historical Loss of Irish Woodlands – Open Journals – 2019

History of Forestry in Ireland – Teagasc – 2020

Time for some home truths about deforestation – The Guardian – 2020

What To Read Next

The Other EV: Eat Vegan

Global meat consumption has trebled since the 1960s and is inherently linked to worsening the Climate Crisis. Going vegan is an important form of climate action and climate justice

Giving Woodland Space To Breath

Discover Ray O’Foghlu's ingenious idea to connect woodland and encourage natural regeneration of forests to help Ireland fight climate change